“…extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.” – Barry Goldwater, July 16, 1964

On the evening of September 7th, 1964, “David and Bathsheba” was the featured film on NBC’s “Monday Night at the Movies.” During one of the commercial breaks there was a striking advertisement, which would become known as the “The Daisy Ad”. It was the most famous television advertisement of the 1964 presidential campaign and probably the most famous presidential ad ever.

On the evening of September 7th, 1964, “David and Bathsheba” was the featured film on NBC’s “Monday Night at the Movies.” During one of the commercial breaks there was a striking advertisement, which would become known as the “The Daisy Ad”. It was the most famous television advertisement of the 1964 presidential campaign and probably the most famous presidential ad ever.

The commercial began by showing a young, freckled girl picking petals off a flower, innocently counting as she picks. As she is about to reach the number ten, the frame freezes and steadily focuses on her right eye as the ominous, slightly echoing voice of an anonymous man counts down until the screen is filled with the powerful flash of light from a detonated atomic bomb. The viewer is left to ponder the consequences of the weapon before hearing a commanding and assured President Lyndon Johnson say, “These are the stakes. To make a world in which all of God’s children will live, or to do into the dark. We must either love each other or we must die.” It concludes by showing “Vote for President Johnson on November 3rd” and an announcer’s words, “The stakes are too high for you to stay home.”

Though it ran only once, the commercial was replayed and spoken about often in a form of free advertising in the immediate aftermath of its controversial showing. It was a political advertisement for President Johnson, but it was undoubtedly about his opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater.

Barry Morris Goldwater was born on New Years Day 1909 in Phoenix, Arizona, three years before it would become the 48th state admitted to the union. He was the grandson of “Big Mike” Goldwasser, a Jewish immigrant who had fled his home in a Russian-controlled area of Poland as a teen and eventually settled in Arizona. “Big Mike” changed his last name to the Americanized Goldwater and enjoyed success as the owner of M. Goldwater and Sons dry goods stores. Barry grew up in Phoenix and was raised in his mother’s Episcopalian faith, a popular kid but indifferent student before his parents sent him to military school in Virginia. He returned to Arizona to attend college, but dropped out to help run the family business after the death of his father.

Goldwater was a successful manager of M. Goldwater and Son’s Phoenix store, but he itched to do other things. He became a self-trained pilot and served in World War II flying non-combat missions. After the war ended, Goldwater came back to Arizona and a few years later agreed to run for a seat on the Phoenix City Council. Three years after winning that election, he ran for and narrowly won election to the U.S. Senate.

In the Senate, Goldwater distinguished himself as a strong and self-proclaimed champion of conservative principles, such as limiting government power and advocating staunch anti-Communism. His profile grew in prominence in 1958, when he was reelected to the Senate and gained notoriety for his book The Conscience of a Conservative. At less than ninety pages, the book was a concentrated and enormously popular (selling over three million copies) expression of vigorous conservative thought that is often credited for helping form the foundation for a conservative political awakening that culminated in the Reagan Revolution over two decades later.

In the Senate, Goldwater distinguished himself as a strong and self-proclaimed champion of conservative principles, such as limiting government power and advocating staunch anti-Communism. His profile grew in prominence in 1958, when he was reelected to the Senate and gained notoriety for his book The Conscience of a Conservative. At less than ninety pages, the book was a concentrated and enormously popular (selling over three million copies) expression of vigorous conservative thought that is often credited for helping form the foundation for a conservative political awakening that culminated in the Reagan Revolution over two decades later.

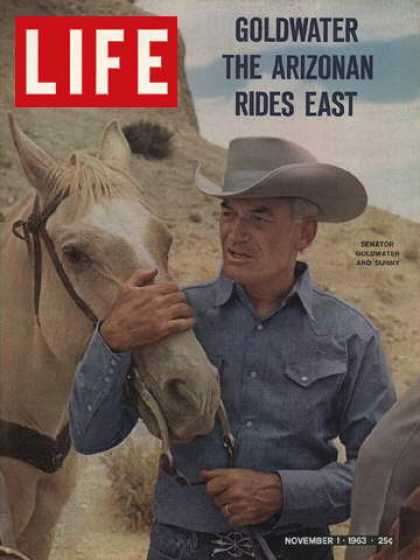

Goldwater’s growing influence was also seen in his stated and largely successful effort to wrest control of the Republican party from the traditional and more moderate Eastern establishment figures to an ambitious group of leaders from the West. From the Arizonan Goldwater–who absorbed criticism and gained admiration for stating, “sometimes I think this country would be better off if we could just saw off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea”–came future conservative presidents from the West, such as Californians Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, and Texan George W. Bush.

By 1964, Goldwater was revered among the political right as, “Mr. Conservative.” In the Republican presidential primaries he offered himself as “a choice, not an echo” as he aggressively took on and defeated Eastern moderates, including Pennsylvania governor William Scranton and New York governor Nelson Rockefeller to earn the party’s nomination.

But his path to the presidency promised to be a perilous one. President Lyndon Johnson enjoyed enormous popularity since taking office following the assassination of President John Kennedy less than a year earlier. Goldwater’s political opponents, including those he vanquished in the Republican primaries, frequently portrayed him as far too dangerous to serve as president, invoking his own words as evidence, such as his 1963 suggestion that atomic weapons could be used to defoliate and expose communist supply routes in Vietnam. This and other examples of Goldwater candor and/or gaffes led some of his aides to urge reporters to, “write what he means, not what he says.”

But his path to the presidency promised to be a perilous one. President Lyndon Johnson enjoyed enormous popularity since taking office following the assassination of President John Kennedy less than a year earlier. Goldwater’s political opponents, including those he vanquished in the Republican primaries, frequently portrayed him as far too dangerous to serve as president, invoking his own words as evidence, such as his 1963 suggestion that atomic weapons could be used to defoliate and expose communist supply routes in Vietnam. This and other examples of Goldwater candor and/or gaffes led some of his aides to urge reporters to, “write what he means, not what he says.”

The 1964 Republican Convention was held in the Cow Palace in San Francisco. In his 1979 autobiography With No Apologies, Goldwater explained, “By the time the convention opened, I had been branded as a fascist, a racist, a trigger-happy warmonger, a nuclear madman and the candidate who couldn’t win.” In his nomination acceptance speech, Goldwater’s outline of his vision for America was largely obscured by a phrase that, more than any other, came to define him. Said Goldwater:

“..the task of preserving and enlarging freedom at home and of safeguarding it from the forces of tyranny abroad is great enough to challenge all our resources and to require all our strength.

Anyone who joins us in all sincerity, we welcome. Those who do not care for our cause, we don’t expect to enter our ranks in any case. And — And let our Republicanism, so focused and so dedicated, not be made fuzzy and futile by unthinking and stupid labels.

I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.

And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.

To Goldwater supporters, this quote reflected the devoted resolve of a great patriot, a kind of modern-day Patrick Henry. But to his opponents and to many of the relatively few undecided voters, Goldwater’s words only added to his image as dangerous ideologue. Johnson trounced Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election in the greatest landslide in American history, winning 61%-39% and carrying every state with the exception of the Republican favorite son’s Arizona and five states in the deep south, where the majority of whites were seething about the president’s promotion of civil rights and voting rights legislation.

To Goldwater supporters, this quote reflected the devoted resolve of a great patriot, a kind of modern-day Patrick Henry. But to his opponents and to many of the relatively few undecided voters, Goldwater’s words only added to his image as dangerous ideologue. Johnson trounced Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election in the greatest landslide in American history, winning 61%-39% and carrying every state with the exception of the Republican favorite son’s Arizona and five states in the deep south, where the majority of whites were seething about the president’s promotion of civil rights and voting rights legislation.

Despite this loss, Goldwater continued to be among the most important Republican political figures of the next two decades. He did not seek reelection to the Senate while he pursued the presidency in 1964, but he did run and win again in 1968 and gained reelection in 1974 and 1980. His most significant act during that time was serving the decisive dose of reality to President Richard Nixon in the final days of Watergate. In his book The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon, historian Stanley Kutler described how Republican leaders in Congress specifically sought out Goldwater because of his stature to explain the desperation of the president’s position. On August 7, 1974, Goldwater privately told Senate colleagues “The best thing [Nixon] can do is get the hell out of the White House…” Later that day he met with Nixon and explained that the president had perhaps four, and no more than ten people in the Senate who might be willing to oppose his conviction on the increasingly likely charges of impeachment. Nixon announced his resignation less than forty-eight hours later.

Suffering from a variety of health ailments, Barry Goldwater retired from the U.S. Senate at the end of his fifth full term in 1986 (his seat was filled by a relative political novice, former Vietnam War prisoner of war John McCain.) Though his body was hobbled, Goldwater’s mind and tongue remained sharp. He continued to express his opinion on several national issues, occasionally surprising and disappointing modern conservatives who felt his views were way out of step with true conservatism.

Suffering from a variety of health ailments, Barry Goldwater retired from the U.S. Senate at the end of his fifth full term in 1986 (his seat was filled by a relative political novice, former Vietnam War prisoner of war John McCain.) Though his body was hobbled, Goldwater’s mind and tongue remained sharp. He continued to express his opinion on several national issues, occasionally surprising and disappointing modern conservatives who felt his views were way out of step with true conservatism.

Goldwater disagreed. In 1994, four years before he died of complications from a stroke at the age of 89, he offered this characteristically strong rebuttal to those who rejected the man known in his time as “Mr. Conservative.” In an interview with the Washington Post, Goldwater said, “When you say ‘radical right’ today, I think of these moneymaking ventures by fellows like Pat Robertson and others who are trying to take the Republican Party away from the Republican Party, and make a religious organization out of it. If that ever happens, kiss politics goodbye.”

On the U.S. military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy preventing open homosexuals from serving in the armed forces, Goldwater noted, “The conservative movement, to which I subscribe, has as one of its basic tenets the belief that government should stay out of people’s private lives. Government governs best when it governs least – and stays out of the impossible task of legislating morality. But legislating someone’s version of morality is exactly what we do by perpetuating discrimination against gays.”

“You don’t have to be straight to be in the military,” the famously direct Goldwater later added, “you just have to shoot straight.”