“We still seek no wider war.” – Lyndon Johnson, August 4, 1964

There were thunderstorms over the Gulf of Tonkin on the evening of August 3, 1964. Two American warships, the USS Maddox and the USS Turner Joy were patrolling the area ten miles off the east coast of North Vietnam. The night before, three North Vietnamese PT boats had attacked the Maddox in retaliation for South Vietnamese commando raids on North Vietnamese military bases on July 31.

There were thunderstorms over the Gulf of Tonkin on the evening of August 3, 1964. Two American warships, the USS Maddox and the USS Turner Joy were patrolling the area ten miles off the east coast of North Vietnam. The night before, three North Vietnamese PT boats had attacked the Maddox in retaliation for South Vietnamese commando raids on North Vietnamese military bases on July 31.

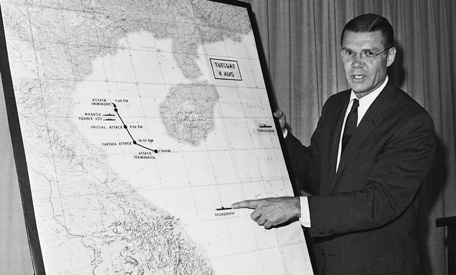

As South Vietnamese boats continued to harass North Vietnamese defenses along the coastline, electronic instruments on the U.S. warships gave readings indicating that another North Vietnamese torpedo attack was underway. The Maddox and the Turner Joy fired on the apparent targets without actually sighting the enemy. Despite the lack of information and the plausible doubts about whether a second North Vietnamese attack was really taking place, President Johnson followed the recommendation of his joint chiefs of staff and Defense secretary Robert McNamara and ordered the first U.S. bombing raid against North Vietnam.

As South Vietnamese boats continued to harass North Vietnamese defenses along the coastline, electronic instruments on the U.S. warships gave readings indicating that another North Vietnamese torpedo attack was underway. The Maddox and the Turner Joy fired on the apparent targets without actually sighting the enemy. Despite the lack of information and the plausible doubts about whether a second North Vietnamese attack was really taking place, President Johnson followed the recommendation of his joint chiefs of staff and Defense secretary Robert McNamara and ordered the first U.S. bombing raid against North Vietnam.

Appearing at a late-night televised press conference on August 4, forty-six years ago this evening, President Johnson publicized what would become known as the Gulf of Tonkin Incident:

“The determination of all Americans to carry out our full commitments to the people and to the government of South Vietnam will be redoubled by this outrage. Yet our response, for the present, will be limited and fitting. We Americans know, although others appear to forget, the risk of spreading conflict. We still seek no wider war.”

Johnson did not mention the covert Central Intelligence Agency role in the July 31 raids or the absence of definitive confirmation of the second North Vietnamese attack. A few days later, concerned that the American destroyers had fired because of confusion and nervousness, Johnson confided to an aide, “Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.” Publicly, however, he displayed no traces of doubt. On August 7, with opinion polls showing that 85 percent of Americans support for an increased U.S. role in Vietnam, President Johnson gained congressional passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. After only forty minutes of deliberation, the House of Representatives unanimously approved the resolution; in the Senate, all but two senators voted for it.

Johnson did not mention the covert Central Intelligence Agency role in the July 31 raids or the absence of definitive confirmation of the second North Vietnamese attack. A few days later, concerned that the American destroyers had fired because of confusion and nervousness, Johnson confided to an aide, “Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.” Publicly, however, he displayed no traces of doubt. On August 7, with opinion polls showing that 85 percent of Americans support for an increased U.S. role in Vietnam, President Johnson gained congressional passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. After only forty minutes of deliberation, the House of Representatives unanimously approved the resolution; in the Senate, all but two senators voted for it.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution provided the president the power to “take all necessary steps, including the use of armed forces” to repel attacks and support allies in Southeast Asia. Although it did not specifically include a declaration of war, President Johnson now possessed wide latitude to commit American troops and resources to Vietnam. This power allowed Johnson to support an anti-Communist ally, to honor the containment-of-Communism policy of his slain predecessor, and to increase his popular appeal during the final months of his presidential campaign against Arizona Republican senator Barry Goldwater.

Reflecting on the questionable events that led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Johnson’s national security adviser Walt Rostow commented shortly after its passage, “We don’t know what happened, but it had the desired result.” Indeed it did. In November, Johnson defeated Goldwater by what was then the largest popular-vote margin in presidential election history, outdistancing his opponent by almost 16 million votes. By the end of 1965, almost two hundred thousand troops American servicemen were in South Vietnam. Within three years, this troop commitment would swell to over half a million.

Reflecting on the questionable events that led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Johnson’s national security adviser Walt Rostow commented shortly after its passage, “We don’t know what happened, but it had the desired result.” Indeed it did. In November, Johnson defeated Goldwater by what was then the largest popular-vote margin in presidential election history, outdistancing his opponent by almost 16 million votes. By the end of 1965, almost two hundred thousand troops American servicemen were in South Vietnam. Within three years, this troop commitment would swell to over half a million.