“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” – Muhammad Ali, April 28, 1967

Today is Muhammad Ali’s 67th birthday. To commemorate it, I am posting this excerpt from my book proposal, Words Mattered: The 200 Quotations That Created, Shaped, and Explain American History.

He was known by many names. Born Cassius Marcellus Clay–the namesake of a Kentucky abolitionist who freed his slaves, including Clay’s ancestors–his relentless talking earned him the mainly affectionate nickname “The Lip.” He called himself “The Greatest” and incredibly backed up that boast with a demonstration of boxing skill that would make him an Olympic gold medalist and a longtime heavyweight champion of the world. Soon after rising to the top of the boxing world, he converted to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. A transcendent figure, Ali was both a sports legend and one of the most incendiary and influential voices of his time, particularly as it related to opposition to the Vietnam War.

He was known by many names. Born Cassius Marcellus Clay–the namesake of a Kentucky abolitionist who freed his slaves, including Clay’s ancestors–his relentless talking earned him the mainly affectionate nickname “The Lip.” He called himself “The Greatest” and incredibly backed up that boast with a demonstration of boxing skill that would make him an Olympic gold medalist and a longtime heavyweight champion of the world. Soon after rising to the top of the boxing world, he converted to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. A transcendent figure, Ali was both a sports legend and one of the most incendiary and influential voices of his time, particularly as it related to opposition to the Vietnam War.

Clay was born and grew up in Louisville. He began boxing at the age of twelve after a policeman responded to Clay’s expressed desire to beat up whomever stole his treasured bicycle by urging him to learn how to fight. Within five years Clay was among the top amateur boxers in the United States. At the age of 18, he won the gold medal in boxing’s light heavyweight division at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. It was in Rome that he began to forge his reputation around the world as possessing rare boxing talent and personal charisma, as he chatted and joked with nearly everyone with whom he came into contact.

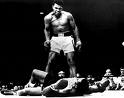

He returned to the United States and won every boxing match over the course of three and a half years, before earning the heavyweight title in February 1964 by defeating Sonny Liston. Just over a year later, he defeated Liston again to defend his title. In addition to the footspeed, quickness, toughness, and guile that he brought into the ring, Clay was renowned for his flamboyant style, including brashly predicting the round that he would finish his opponent, ridiculing his opponents, and engaging in unprecedented self-promotion, that some considered fun-loving and others considered obnoxious.

He returned to the United States and won every boxing match over the course of three and a half years, before earning the heavyweight title in February 1964 by defeating Sonny Liston. Just over a year later, he defeated Liston again to defend his title. In addition to the footspeed, quickness, toughness, and guile that he brought into the ring, Clay was renowned for his flamboyant style, including brashly predicting the round that he would finish his opponent, ridiculing his opponents, and engaging in unprecedented self-promotion, that some considered fun-loving and others considered obnoxious.

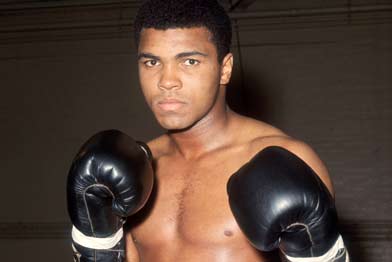

After beating Liston to become champion, Clay joined the black nationalist movement the Nation of Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. In 1966, Ali–who was still regularly referred to by his birth name, which he called his “slave name”–was informed that he had been drafted into the Army as part of an escalation in American troop levels in Vietnam. Ali refused induction on the basis of his religious beliefs as a minister of Islam. Three years later, after failed legal appeals including one to the U.S. Supreme Court, Ali formally refused induction into the U.S. military, soon adding, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” and “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

After beating Liston to become champion, Clay joined the black nationalist movement the Nation of Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. In 1966, Ali–who was still regularly referred to by his birth name, which he called his “slave name”–was informed that he had been drafted into the Army as part of an escalation in American troop levels in Vietnam. Ali refused induction on the basis of his religious beliefs as a minister of Islam. Three years later, after failed legal appeals including one to the U.S. Supreme Court, Ali formally refused induction into the U.S. military, soon adding, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” and “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

He was arrested for draft evasion and two months later was convicted by a jury after twenty minutes of deliberation. Ali was sentenced to a $10,000 fine, five years imprisonment, and he was stripped of his championship title and his license to box. Ali never served jail time and he earned money by lecturing against the Vietnam War on college campuses as appeals to the conviction eventually worked their way to the United States Supreme Court, which unanimously found in his favor in June 1971.

Ali’s reigned as boxing’s world heavyweight champion for most of the period between 1964-1978, with the exceptions of two brief periods following defeats and the one nearly four year span when he was stripped of his title and had his license suspended due to his refusal to be inducted into the U.S. Army. Surveys in the mid-1970s listed Ali as the most famous person in the world and testimony of this international appeal is found with his being named Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the 20th Century and as the Sports Personality of the Century by the British Broadcasting Company.

Ali’s reigned as boxing’s world heavyweight champion for most of the period between 1964-1978, with the exceptions of two brief periods following defeats and the one nearly four year span when he was stripped of his title and had his license suspended due to his refusal to be inducted into the U.S. Army. Surveys in the mid-1970s listed Ali as the most famous person in the world and testimony of this international appeal is found with his being named Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the 20th Century and as the Sports Personality of the Century by the British Broadcasting Company.

But Ali’s lasting impact away from boxing is also profound to American history and culture. David Remnick, a Pulitzer Prize winning writer who authored the Ali biography King of the World, noted of the boxing champion’s stand against the Vietnam War, “As he had before and would again, Ali had showed his gift for intuitive action, for speed, and this time he was acting in a way that would characterize the era itself, a resistance to authority, an insistence that national loyalty was not automatic or absolute. His rebellion, which started out as racial, now had widened in scope.”

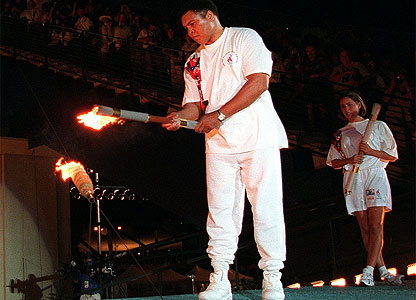

At the opening ceremonies of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta Ali–ravaged by Parkinson’s disease of his fast, smooth and powerful speech and movement–carried the torch the final distance of its global journey. Though many had not and would not ever forgive him for failing to serve his country when called in time of war, most Americans at this time viewed Ali as an admirable, even beloved figure, who had demonstrated unrivaled greatness in the ring and impressive perseverance outside it. Ali struggled to steady his hand, his face absent any of the expression that had marked his rise as an international icon, as he lit the flame that started the games, a generation after doing more than any other individual to spark domestic opposition to the Vietnam War.

At the opening ceremonies of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta Ali–ravaged by Parkinson’s disease of his fast, smooth and powerful speech and movement–carried the torch the final distance of its global journey. Though many had not and would not ever forgive him for failing to serve his country when called in time of war, most Americans at this time viewed Ali as an admirable, even beloved figure, who had demonstrated unrivaled greatness in the ring and impressive perseverance outside it. Ali struggled to steady his hand, his face absent any of the expression that had marked his rise as an international icon, as he lit the flame that started the games, a generation after doing more than any other individual to spark domestic opposition to the Vietnam War.