“There was never a good war or a bad peace.” – Benjamin Franklin, 1783

Today is the 232nd anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and of Alliance Between France and the United States. To commemorate the critical importance of this treaty in America’s victory over the British in the Revolutionary War, and to recognize the key role Benjamin Franklin had in its creation, I am publishing this excerpt from my book proposal, Words Mattered: The 200 Quotations That Shaped, Reflected, and Explain America.

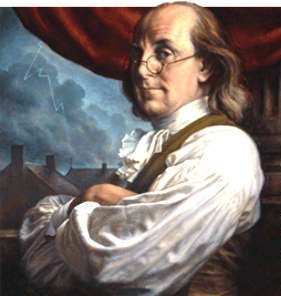

The shocking victory of the American colonists over the British at Yorktown and their ultimate triumph in the Revolutionary War resulted in large measure from the valor of soldiers and the planning of officers. But in addition to these critical factors, the colonists had won their independence because of a man whose service during the war never included carrying a musket in battle or issuing a military command. Instead, Benjamin Franklin shrewdly, tirelessly, and brilliantly pursued aid for the revolutionary cause and then applied those same traits to ensure sustenance for the infant nation of the United States of America.

As the American ambassador to France, Franklin served as the Revolution’s greatest salesman, a master politician who relentlessly sought to persuade the reluctant French that it was in their best interest to support the struggling American resistance. Franklin cultivated his image among the French as the liberty-loving frontier sage to build momentum for what he knew would be essential support for beating the British.

As the American ambassador to France, Franklin served as the Revolution’s greatest salesman, a master politician who relentlessly sought to persuade the reluctant French that it was in their best interest to support the struggling American resistance. Franklin cultivated his image among the French as the liberty-loving frontier sage to build momentum for what he knew would be essential support for beating the British.

When the Americans emerged victorious from the Battle of Saratoga, Franklin seized on his enormous popularity in France to meet with French king Louis XVI and convinced him to provide the money, materials, and soldiers that proved indispensable to eventual American success. Buoyed by the backing of one of the world’s superpowers, Franklin wrote to a friend, “Your troubles will not last much longer. We have formed a treaty with the French! This alliance will serve to keep the English Bull quiet and make him behave himself. His horns have been shortened.”

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, Franklin served as a chief negotiator of the Treaty of Paris. Signed in 1783 (and shown in the painting to the left; unfinished because the British delegation refused to participate in a portrayal of the agreement), this treaty formally ended the war and established boundaries and economic agreements that would prove very beneficial to the new nation. A week after the treaty was signed, Franklin reflected on the tragedy of the war and on the hope that its end would bring. He wrote to a friend, “There was never a good war or a bad peace.”

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, Franklin served as a chief negotiator of the Treaty of Paris. Signed in 1783 (and shown in the painting to the left; unfinished because the British delegation refused to participate in a portrayal of the agreement), this treaty formally ended the war and established boundaries and economic agreements that would prove very beneficial to the new nation. A week after the treaty was signed, Franklin reflected on the tragedy of the war and on the hope that its end would bring. He wrote to a friend, “There was never a good war or a bad peace.”

In the last few years of his life, Franklin endorsed the dismantling of slavery. He became president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and published a sharp parody rebuking proslavery arguments. During the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Franklin’s antislavery position led a South Carolina delegate to charge that “even great men have their senile moments.” A Pennsylvania delegate indignantly responded that “the qualities of his soul, as well as those of his mind, are yet in their vigour” and that Franklin was still uniquely able “to speak the language of America, and to call us back to our first principles.”

Benjamin Franklin, considered America’s founding grandfather by many, died on April 17, 1790, at the age of eighty-four. An estimated twenty thousand people attended his funeral to pay respects to the man and to the immeasurable impact he had on the creation of the United States and the formation of an American identity. When word of Franklin’s death reached France, Count Mirabeau stood before the French National Assembly and mourned the loss of his American friend, calling him “a mighty genius . . . able to restrain alike thunderbolts and tyrants.”

Benjamin Franklin, considered America’s founding grandfather by many, died on April 17, 1790, at the age of eighty-four. An estimated twenty thousand people attended his funeral to pay respects to the man and to the immeasurable impact he had on the creation of the United States and the formation of an American identity. When word of Franklin’s death reached France, Count Mirabeau stood before the French National Assembly and mourned the loss of his American friend, calling him “a mighty genius . . . able to restrain alike thunderbolts and tyrants.”