“…an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” – Winston Churchill, March 5, 1946

Winston Churchill had an unique and lifelong connection to the United States. His fascinating mother was born Jennie Jerome in Brooklyn and was one of many American heiresses in the late 19th century who traveled across the Atlantic before marrying into European aristocracy. As British prime minister in the years before American entry into World War II, Churchill cultivated a strong bond of affection and necessity with President Franklin Roosevelt, with whom he forged the “special relationship” that is still often referred to by modern leaders of these two great nations. Churchill’s exceptional bond to America was recognized in 1963, when President John Kennedy signed a congressional proclamation that conferred honorary U.S. citizenship on Churchill, making him just the second person–following Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette–to earn such distinction.

Winston Churchill had an unique and lifelong connection to the United States. His fascinating mother was born Jennie Jerome in Brooklyn and was one of many American heiresses in the late 19th century who traveled across the Atlantic before marrying into European aristocracy. As British prime minister in the years before American entry into World War II, Churchill cultivated a strong bond of affection and necessity with President Franklin Roosevelt, with whom he forged the “special relationship” that is still often referred to by modern leaders of these two great nations. Churchill’s exceptional bond to America was recognized in 1963, when President John Kennedy signed a congressional proclamation that conferred honorary U.S. citizenship on Churchill, making him just the second person–following Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette–to earn such distinction.

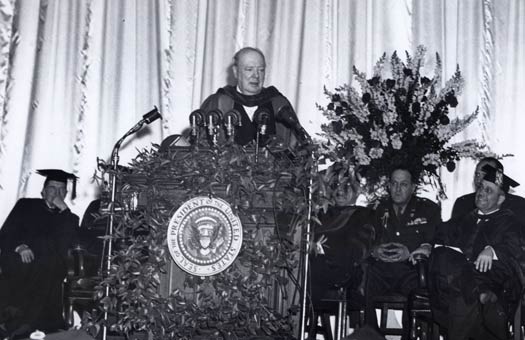

Yet Churchill’s most enduring link to the United States may be an address he delivered 64 years ago today at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. It was immediately and remains known as the the Iron Curtain Speech.

Churchill traveled to the United States in January of 1946, less than six months after British voters–appreciative and admiring of his wartime leadership but weary of battle and focused on economic concerns–ousted his Conservative Party from power in British parliamentary elections, resulting in his resignation as prime minister of Great Britain (he remained the Conservative leader and returned as prime minister from 1951-55.) During his two-month stay in the U.S., Churchill addressed the Virginia General Assembly, met with General Dwight Eisenhower, and visited the grave of his close friend and colleague, Franklin Roosevelt, who had died less than a year earlier. During this visit, Churchill famously noted of FDR, “Meeting Roosevelt was like uncorking your first bottle of champagne.”

Churchill traveled to the United States in January of 1946, less than six months after British voters–appreciative and admiring of his wartime leadership but weary of battle and focused on economic concerns–ousted his Conservative Party from power in British parliamentary elections, resulting in his resignation as prime minister of Great Britain (he remained the Conservative leader and returned as prime minister from 1951-55.) During his two-month stay in the U.S., Churchill addressed the Virginia General Assembly, met with General Dwight Eisenhower, and visited the grave of his close friend and colleague, Franklin Roosevelt, who had died less than a year earlier. During this visit, Churchill famously noted of FDR, “Meeting Roosevelt was like uncorking your first bottle of champagne.”

The Iron Curtain Speech (video and text) was described in a 2006 American Heritage article by writer and editor Christine Gibson as, “a quintessential Churchill speech, one that was bold, expertly written, and prophetic.” As he had about ten years earlier, Churchill accurately warned of a growing European menace; this time from aggression of communist Soviet Union, a nation whose sacrifice and alliance had so recently proven critical in defeating the scourge of Nazi Germany.

The Iron Curtain Speech (video and text) was described in a 2006 American Heritage article by writer and editor Christine Gibson as, “a quintessential Churchill speech, one that was bold, expertly written, and prophetic.” As he had about ten years earlier, Churchill accurately warned of a growing European menace; this time from aggression of communist Soviet Union, a nation whose sacrifice and alliance had so recently proven critical in defeating the scourge of Nazi Germany.

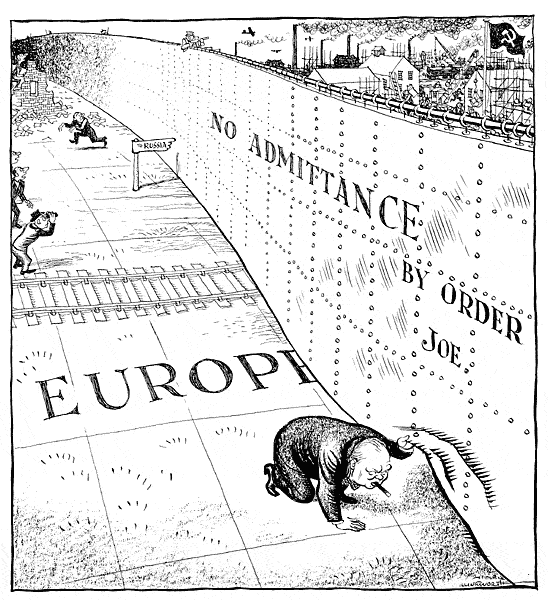

In the speech, Churchill referenced his admiration and appreciation for the Soviets while simultaneously sending a clarion call for Anglo-American unity and steadfastness in negotiating with and confronting them. He also provided the world with the term that would endure as the vivid metaphor for communist totalitarianism for the nearly half century struggle of the Cold War:

I have a strong admiration and regard for the valiant Russian people and for my wartime comrade, Marshal Stalin. There is deep sympathy and goodwill in Britain — and I doubt not here also — toward the peoples of all the Russias and a resolve to persevere through many differences and rebuffs in establishing lasting friendships.

I have a strong admiration and regard for the valiant Russian people and for my wartime comrade, Marshal Stalin. There is deep sympathy and goodwill in Britain — and I doubt not here also — toward the peoples of all the Russias and a resolve to persevere through many differences and rebuffs in establishing lasting friendships.

It is my duty, however, to place before you certain facts about the present position in Europe.

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia; all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject, in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in some cases increasing measure of control from Moscow…

Churchill proceeded to issue a typically articulate and clear-minded assessment of the threat posed by the Soviets as well as a stern, historically-based warning of the perils that would arise if the threat was ignored.

I do not believe that Soviet Russia desires war. What they desire is the fruits of war and the indefinite expansion of their power and doctrines.

I do not believe that Soviet Russia desires war. What they desire is the fruits of war and the indefinite expansion of their power and doctrines.

But what we have to consider here today while time remains, is the permanent prevention of war and the establishment of conditions of freedom and democracy as rapidly as possible in all countries. Our difficulties and dangers will not be removed by closing our eyes to them. They will not be removed by mere waiting to see what happens; nor will they be removed by a policy of appeasement.

What is needed is a settlement, and the longer this is delayed, the more difficult it will be and the greater our dangers will become.

From what I have seen of our Russian friends and allies during the war, I am convinced that there is nothing they admire so much as strength, and there is nothing for which they have less respect than for weakness, especially military weakness.

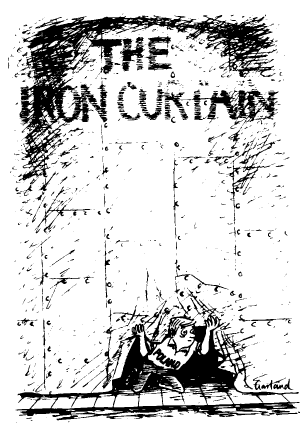

Churchill’s speech was met with broad approval within the United States and Great Britain. Unsurprisingly the Soviets, including premeir Josef Stalin who termed it “war mongering”, were not as supportive. Regardless of one’s opinion, Churchill’s speech–like many others delivered by one of the greatest orators in modern history–met its intended effect. The term “iron curtain” provided people around the world with a sharp, memorable, and succinct yet thorough description of a new danger in Europe.

Ousted from office and thousands of miles away from home, Churchill and his words had again inspired and mobilized vigilance, courage, and action from his audience, which would even decades after his death in 1965, come to include countless millions throughout Europe and his beloved United States.

(Photos from top: Churchill and President Truman are welcomed in Missouri; Churchill and Eleanor Roosevelt visit FDR’s grave; Churchill delivers Iron Curtain Speech; British cartoon from 1946 showing Churchill exposing Iron Curtain; British cartoon from 1980 depicting Poland emerging from under Iron Curtain.)