“I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt, April 12, 1945

President Franklin D. Roosevelt returned from Yalta, the southern Ukrainian city on the north coast of the Black Sea, after an enormously consequential “Big Three” summit in late February of 1945. Two days later, on March 1, he addressed a joint session of Congress while seated, and for the first and only time during his presidency, noted the physical disabilities brought on by his decades long battle with polio. With characteristic cheeriness, Roosevelt said to his congressional audience and the millions of Americans listening on radios:

President Franklin D. Roosevelt returned from Yalta, the southern Ukrainian city on the north coast of the Black Sea, after an enormously consequential “Big Three” summit in late February of 1945. Two days later, on March 1, he addressed a joint session of Congress while seated, and for the first and only time during his presidency, noted the physical disabilities brought on by his decades long battle with polio. With characteristic cheeriness, Roosevelt said to his congressional audience and the millions of Americans listening on radios:

I hope that you will pardon me for an unusual posture of sitting down during the presentation of what I want to say. I know that you will realize that it makes it a lot easier for me in not having to carry about 10 pounds of steel around on the bottom of my legs, and also because of the fact that I have just completed a 14,000-mile trip.

This remarkable example of candor from Roosevelt was a disarming indication of how significantly his health had declined during the first few months of his unprecedented fourth term as president and the words were met by strong applause. Although he had been in office longer than any previous president, Roosevelt was only 63 years old at the time of the speech, but the intense stress of his job–particularly during the great crises of the Depression and World War II–had taken a powerful toll on him. Roosevelt’s eyes were deeper set and he had clearly lost a great deal of weight, making him appear frail.

Roosevelt was clear and effective during this address, in which he explained the purposes and outcomes of what he called the Crimea Conference. He described the challenges and the plans to address them made by himself, British prime minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet premier Josef Stalin for the keenly anticipated–and soon-to-be-realized–Allied victory in World War II.

Exactly four weeks after the speech, Roosevelt left for a planned two-week respite at the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia. Roosevelt had traveled to this small resort town located about 50 miles south of Atlanta for over 20 years since learning of the recuperative reputation of its natural spring waters that reached eighty-six degrees year-round. Within a week those with him, including his cousin Margaret “Daisy” Suckley, Lucy Rutherfurd (his mistress when she was Lucy Mercer; she had been Eleanor Roosevelt’s social secretary 25 years earlier when FDR was secretary of the Navy and since being widowed had rekindled a relationship with Roosevelt), and Rutherfurd’s friend Elizabeth Shoumatoff.

Exactly four weeks after the speech, Roosevelt left for a planned two-week respite at the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia. Roosevelt had traveled to this small resort town located about 50 miles south of Atlanta for over 20 years since learning of the recuperative reputation of its natural spring waters that reached eighty-six degrees year-round. Within a week those with him, including his cousin Margaret “Daisy” Suckley, Lucy Rutherfurd (his mistress when she was Lucy Mercer; she had been Eleanor Roosevelt’s social secretary 25 years earlier when FDR was secretary of the Navy and since being widowed had rekindled a relationship with Roosevelt), and Rutherfurd’s friend Elizabeth Shoumatoff.

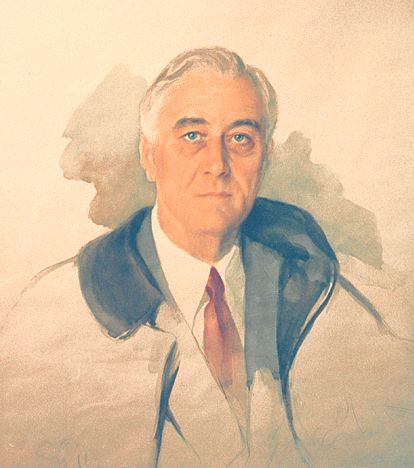

Roosevelt was sitting for a portrait that was being painted by the artist Shoumatoff for her daughter (pictured left, unfinished.) He was working on an upcoming speech, which would have included a sentence, “The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today” that echoed perhaps his most famous words. He also was signing various documents, including the extension of the Commodity Credit Corporation, joking to the women after applying his signature with a flourish, “There is where I make a law.”

In her book No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II , historian Doris Kearns Goodwin recounts the details of what happened next:

At one o’clock, the butler came in to set the table for lunch. Roosevelt glanced at his watch and said, “We’ve got just fifteen minutes more.” Then, suddenly, Shoumatoff recalled, “he raised his right hand and passed it over his forehead several times in a strange jerky way.” Then his head went forward. Thinking he was looking for something, Suckley went over to him and asked if he had dropped his cigarette. “He looked at me,” Suckely recalled, “his forehead furrowed with pain, and tried to smile. He put his left hand up to the back of his head and said, ‘I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.’ And then he collapsed.”

President Roosevelt had suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He was carried by his valet and butler into a bedroom. Despite quick and desperate efforts by doctors to save him, including artificial respiration and a shot of adrenaline to his heart, Roosevelt never regained consciousness. He was pronounced dead at 3:35.

Eleanor Roosevelt was at a reception in Washington, DC when she was called to the phone and asked by Roosevelt’s press secretary Steve Early to come immediately to the White House. She recalled, “I got into the car and sat with clenched hands all the way to the White House. In my heart I knew what had happened, but one does not actually formulate these terrible thoughts until they are spoken.” Upon hearing the news of Roosevelt’s death, Churchill said, “I felt as if I had been struck by a physical blow.” U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union Averill Harriman drove to the Kremlin to inform Stalin, who according to Harriman appeared “deeply distressed” and, reflecting much about his own personality and conception of political power, expressed concern that Roosevelt might have been poisoned.

Across the United States, most citizens reacted with profound sadness. Roosevelt was returned to Washington on a train, which passed the roads of cities and towns that were lined with mourners at all hours. When the funeral train arrived in Washington, General George Marshall’s wife Katherine recalled, “The streets were lined on both sides with troops. In back of them could be seen the faces of the crowds. At each intersection the crowds extended down the side streets as far as you could see. Complete silence spread like a pall over the city, broken only by the funeral dirge and the sobs of the people.”

Across the United States, most citizens reacted with profound sadness. Roosevelt was returned to Washington on a train, which passed the roads of cities and towns that were lined with mourners at all hours. When the funeral train arrived in Washington, General George Marshall’s wife Katherine recalled, “The streets were lined on both sides with troops. In back of them could be seen the faces of the crowds. At each intersection the crowds extended down the side streets as far as you could see. Complete silence spread like a pall over the city, broken only by the funeral dirge and the sobs of the people.”

Before Roosevelt’s funeral procession left for Washington and his eventual burying place of Hyde Park, New York, his body was carried by hearse to Georgia Hall on the campus of the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, a hospital for polio patients founded by Roosevelt in 1927. Whenever he left Warm Springs as president, Roosevelt would stop here to bid farewell to the patients until his return. An accordionist who had played several times for President Roosevelt, Graham Jackson, played Dvorak’s “Going Home” and the Christian hymn “Nearer My God to Me”.

Before Roosevelt’s funeral procession left for Washington and his eventual burying place of Hyde Park, New York, his body was carried by hearse to Georgia Hall on the campus of the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, a hospital for polio patients founded by Roosevelt in 1927. Whenever he left Warm Springs as president, Roosevelt would stop here to bid farewell to the patients until his return. An accordionist who had played several times for President Roosevelt, Graham Jackson, played Dvorak’s “Going Home” and the Christian hymn “Nearer My God to Me”.

Jackson’s tear-streaked face, captured in the iconic Life magazine photo by Ed Clark (left) reflected the feelings of those gathered at Georgia Hall that day as well as those of millions across the United States and the world who mourned the loss of President Franklin Roosevelt, the man who helped lift America from the Great Depression and protect the world from tyranny.

Pingback from Most known&meaningful melodies ever

Time July 26, 2012 at 2:36 am

[…] Originally Posted by Manxfeeder In America, the theme from Dvorak's New World Symphony fits, since it has become a spiritual, Going Home. I can't find the picture, but there is a moving photograph of a black man in tears watching JFK's funeral procession and, on his accordion, playing Going Home. Found it for you (it was Rooselvelt's funeral actually). grahm1.jpg Link. […]