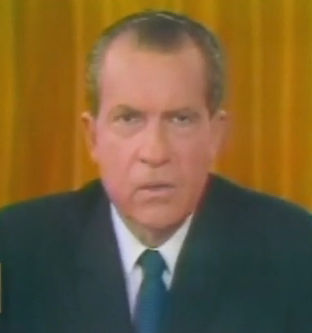

“…the great silent majority…” – Richard Nixon, November 3, 1969

40 years ago today, four students protesting the President Nixon’s Vietnam War policies were killed by members of the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University. Following is an excerpt from my book proposal, Words Mattered: The 200 Quotations That Shaped, Reflected, and Explain America that explains this incident and explores the significance and impact of Nixon’s use of the term “great silent majority” during his first term as president.

Following his razor-thin victory over Vice President Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential election, Richard Nixon found himself in the same paradoxical position as his predecessor: the leader of the most powerful nation in the world seeking a way not to become the first American president to lose a war. Believing that simply withdrawing would be an inexcusable abandonment of South Vietnam and a sign that the United States would no longer keep its word to its allies, Nixon pursued what he called an “honorable end” to the conflict.

However, Nixon’s early engagement with the Vietnam War was marked by continued casualties in Southeast Asia and mounting division at home. In October 1969, less than nine months after Nixon’s inauguration, the largest antiwar demonstrations in U.S. history, known collectively as the Moratorium, were held in cities across the nation. While viewing the over 200,000 protesters congregated on the Washington Mall, Nixon commented to an aide, ”I simply cannot permit foreign policy to be made in the streets of Washington.”

Buoyed by polls indicating that nearly 60% of Americans supported his Vietnam policies, Nixon took the offensive with a televised address, which he insisted on writing himself. In his speech, the largely untested new president sought to demonstrate his strength to the North Vietnamese and to delineate a new course in policy. He laid out a plan, that would later be called “Vietnamization”: the United States would gradually reduce its troop commitment while strengthening the role of the South Vietnamese military and expanding pacification strategies aimed at winning the hearts and minds of South Vietnamese villagers with political, social, and economic reforms. But the address is best remembered for Nixon’s sharp rebuke of protesters, whose voices and influence were becoming a growing nuisance and concern for the president:

Buoyed by polls indicating that nearly 60% of Americans supported his Vietnam policies, Nixon took the offensive with a televised address, which he insisted on writing himself. In his speech, the largely untested new president sought to demonstrate his strength to the North Vietnamese and to delineate a new course in policy. He laid out a plan, that would later be called “Vietnamization”: the United States would gradually reduce its troop commitment while strengthening the role of the South Vietnamese military and expanding pacification strategies aimed at winning the hearts and minds of South Vietnamese villagers with political, social, and economic reforms. But the address is best remembered for Nixon’s sharp rebuke of protesters, whose voices and influence were becoming a growing nuisance and concern for the president:

“And so tonight to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans, I ask for your support,… for the more divided we are at home, the less likely the enemy is to negotiate …. Let us be united for peace. Let us also be united against defeat. Because let us understand: North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.”

Reaction to the speech was intense. Over 80,000 letters and telegrams were sent to the White House, overwhelmingly in support of the president. Approval ratings for President Nixon climbed to 81% by early December, thirty percentage points higher than they had been just two months earlier. But Nixon’s rise in overall approval was accompanied by an increasing intensity in the organized protest against his policy for the Vietnam War.

On April 30, 1970, Nixon announced that U.S. and South Vietnamese forces had attacked Communist sanctuaries and supply routes in Cambodia. Defending the action, Nixon stated, “If when the chips are down, the world’s most powerful nation, the United States of America, acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world.” To the president’s most vocal detractors, the invasion of what seemed to many to be a neutral country was an outrageous and immoral escalation of a war he had promised to end. The morning after he announced the Cambodian incursion, Nixon referred to his detractors–many of whom were activist college students–as “bums…blowing up campuses.”

Four days later, the divisive domestic conflict over the Vietnam War reached unprecedented depths on the Akron, Ohio campus of Kent State University. The Ohio National Guard had been ordered by the governor to Kent State to help maintain order in the face of anti-war protests composed mainly of students. Members of a company of the Ohio National Guard, confused in the haze of teargas and believing that they were trapped by protesters who were hurling rocks and profane insults in their direction, fired a total of sixty-seven shots in less than a quarter of a minute. Thirteen students were shot, one was paralyzed, and four were killed. Upon leaving the morgue after identifying the body of his daughter, Arthur Krause, the father of slain protester Allison Krause said, “My daughter was not a bum.”

Four days later, the divisive domestic conflict over the Vietnam War reached unprecedented depths on the Akron, Ohio campus of Kent State University. The Ohio National Guard had been ordered by the governor to Kent State to help maintain order in the face of anti-war protests composed mainly of students. Members of a company of the Ohio National Guard, confused in the haze of teargas and believing that they were trapped by protesters who were hurling rocks and profane insults in their direction, fired a total of sixty-seven shots in less than a quarter of a minute. Thirteen students were shot, one was paralyzed, and four were killed. Upon leaving the morgue after identifying the body of his daughter, Arthur Krause, the father of slain protester Allison Krause said, “My daughter was not a bum.”

President Nixon responded to the Kent State incident with a brief statement that began, “This should remind us all once again that when dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy.” Nixon met with Kent State students and even embarked on an unscheduled, pre-dawn visit to anti-war demonstrators who had gathered in Washington, D.C. to discuss what aides described as, “the ‘war thing’ and other topics.” The stunned student protesters became even more baffled when Nixon sought to talk with one young man about college football and with another about surfing.

In the Fall of 1970, a presidential commission studying Kent State criticized the irresponsibility of some university administrators and faculty and the recklessness and violence of some students, but concluded that the killings were, “unnecessary and unwarranted.” A few months earlier, however, Nixon expressed his belief that the Kent State tragedy had provided him with a political opportunity. H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s Chief of Staff, noted in his diary, “[President] thinks now the college demonstrators have overplayed their hands…evidence is the blue collar group rising against them, and P [President] can mobilize them.” Two years later, President Nixon won reelection over Democratic challenger Senator George McGovern in an overwhelming landslide, winning almost 61% of the total vote and 49 of 50 states.

The powerful engine of Nixon’s enormous victory was the Silent Majority, which–until being recognized in the president’s speech–had felt increasingly ignored and besieged, even resentful and fearful. In his 2008 book Nixonland, historian Rick Pearlstein noted a Time Magazine profile of the Silent Majority from 1969 that described them as “not so much shrill as perplexed…[possessing] a civics-book sense of decency.” Reflecting on this characterization within the context of Kent State and other domestic turmoil that followed, Pearlstein wrote, “Pity poor Time, whose America was but a memory.”