“The hopes and prayers of liberty loving people everywhere march with you.” – Dwight Eisenhower, June 6, 1944

The term D-Day is, as it should be, among the most familiar in American history. Its audacity and importance cannot be overstated. The greatest military invasion the world had ever seen–launched 66 years ago today–was secretly planned from almost immediately after the fall of France and would eventually liberate millions of Europeans from the murderous clutches of Nazi Germany.

The term D-Day is, as it should be, among the most familiar in American history. Its audacity and importance cannot be overstated. The greatest military invasion the world had ever seen–launched 66 years ago today–was secretly planned from almost immediately after the fall of France and would eventually liberate millions of Europeans from the murderous clutches of Nazi Germany.

Knowing as we do the ultimate success of the D-Day invasion, codenamed “Operation Overlord”, can lead to the false impression that it was a certain or even a likely victory for the allied forces. But any study of D-Day inevitably leads to a reflection on its most salient characteristic: unpredictability.

A plan that closely resembled the D-Day invasion was approved by British prime minister Winston Churchill and U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt at their conference in Quebec in August, 1943. Four months later, the two leaders met in Tehran with Soviet premier Josef Stalin (who was traveling outside the Soviet Union for the first time in over 30 years) and again advanced details of an invasion of the European continent from across the English Channel. Stalin pushed Churchill and Roosevelt to determine who would lead such a critical and ambitious endeavor and soon American General Dwight Eisenhower was named the Commander of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF.)

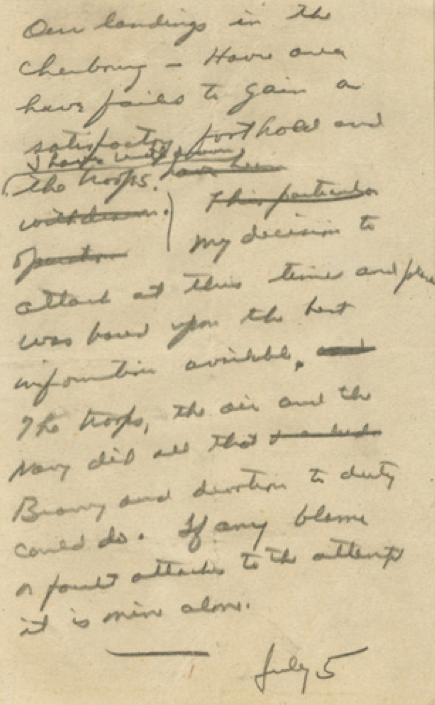

In the remarkably short span of six months, over 160,000 Allied troops were amassed in southern England preparing for the D-Day invasion. The largest armada in world history, consisting of over 7,000 American, British, and Canadian naval vessels were also prepared for battle, as were over 10,000 planes that would drip airborne troops and seek to pound the certain German resistance. Charged with deciding the optimal time for an invasion was Eisenhower, who struggled with the complications caused by uncertain weather forecasts, tidal conditions, and varying opinions among top advisers. Amid horizontal sheets or rain and gale force winds on June 5, he decided to launch the invasion in the predawn hours of the following day. Later on June 5, he drafted a quick note (mistakenly dated July 5 and shown at left) that reflected the enormous uncertainty of the decision he had just made and its potentially monumental consequences.

In the remarkably short span of six months, over 160,000 Allied troops were amassed in southern England preparing for the D-Day invasion. The largest armada in world history, consisting of over 7,000 American, British, and Canadian naval vessels were also prepared for battle, as were over 10,000 planes that would drip airborne troops and seek to pound the certain German resistance. Charged with deciding the optimal time for an invasion was Eisenhower, who struggled with the complications caused by uncertain weather forecasts, tidal conditions, and varying opinions among top advisers. Amid horizontal sheets or rain and gale force winds on June 5, he decided to launch the invasion in the predawn hours of the following day. Later on June 5, he drafted a quick note (mistakenly dated July 5 and shown at left) that reflected the enormous uncertainty of the decision he had just made and its potentially monumental consequences.

Wrote Eisenhower in the case of a failed invasion:

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

On the afternoon of June 5, Eisenhower met with Allied troops, to whom he would address in pre-battle banter and later in another message.

On the afternoon of June 5, Eisenhower met with Allied troops, to whom he would address in pre-battle banter and later in another message.

Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon a great crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers in arms on other fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened, he will fight savagely.

But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man to man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our home fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to victory!

I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full victory!

Good Luck! And let us all beseech the blessings of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.

Eisenhower’s message is brief (fewer than 250 words), sober (“Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened, he will fight savagely”), and inspiring (“But this is the year of 1944!…The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to victory!”) They are words that, by themselves, could not and would not achieve Allied victory, the liberation of brutalized people and nations, and eventually the end of World War II in Europe. But they eloquently frame the task faced by the Allies and serve as reminders of their historic bravery and sacrifice.

Eisenhower’s message is brief (fewer than 250 words), sober (“Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened, he will fight savagely”), and inspiring (“But this is the year of 1944!…The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to victory!”) They are words that, by themselves, could not and would not achieve Allied victory, the liberation of brutalized people and nations, and eventually the end of World War II in Europe. But they eloquently frame the task faced by the Allies and serve as reminders of their historic bravery and sacrifice.

On June 6, 1944, the most recent and reliable estimates place the total number of Allied casualties at over 10,000, with over 4,000 killed, 2,500 of them Americans. Largely because of their sacrifice, over 300,000 Allied soldiers would enter within a week and the German war machine would be destroyed within a year.