“And we have now with horror seen the discovery of such witchcraft!” – Cotton Mather, 1693

America’s intrigue with witches far precedes the popular celebration of Halloween, the premier of “The Wizard of Oz”, or even the foundation of the United States as an independent country. More than any other episode in history, Americans are captivated with stories of witchcraft because of the wave of murderous hysteria that washed over Salem Village, Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1692, known as the Salem Witchcraft Trials.

America’s intrigue with witches far precedes the popular celebration of Halloween, the premier of “The Wizard of Oz”, or even the foundation of the United States as an independent country. More than any other episode in history, Americans are captivated with stories of witchcraft because of the wave of murderous hysteria that washed over Salem Village, Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1692, known as the Salem Witchcraft Trials.

The conception of witches who secretly and sinisterly enter into partnerships with the devil is evident in the Old Testament, though there is little evidence of widespread persecution of suspected witches until the 13th century. Over the next 200 years, papal inquisitions into heretics led to a greater emphasis and more detailed definition of what would become commonly characterized as witchcraft. In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII blamed witchcraft for crop failure and infant mortality in Germany and commissioned two friars to investigate.

Two years later these friars issued, Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) that countered the widely-held belief that witches were powerless against God’s strength and asserted that it was the duty of Christians to seek out witches and kill them. The book served as a kind of manual for pursuing and handling cases of witchcraft for the next two centuries when spasms of witchcraft hysteria gripped parts of Europe and resulted in the death of tens of thousands of suspected witches, most of whom were women.

Although concern with witchcraft had peaked in Europe decades before Puritans fled England for religious freedom in the New World, many of those who settled in Salem Village still retained deep fears of possession by the devil. These fears were exacerbated due to the enormously difficult conditions of early colonial life. Managing to find and make enough food to survive was an arduous task in the rocky terrain and harsh climate of New England. Sickness, particularly smallpox, was rampant and along with death, it brought a desperate compulsion to explain its curses.

Social and economic tensions also strained those in Salem Village. King William’s War, initiated by England in North America against the French, caused great destruction and led to the flood of refugees–and increased competition for resources– into the already struggling area. Resentments between the more prosperous merchant class in the port area of Salem Town and the poorer farmers of Salem Village also grew, with many of the residents of Salem Village expressing concern that the worldliness and affluence was of Salem Town was a threat to the Puritan values of simplicity, hard work, and total obedience to God.

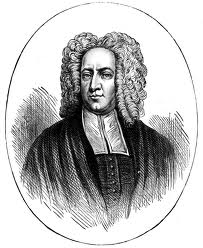

The typically strict application of the Puritan code was reflected in many ways: the dark and somber style of dress, the repression of opinions and emotions, and the conviction that all sins were to be punished. Consistent with this often rigid code were the beliefs that if a neighbor suffered crop failure or the death of an infant, it was “God’s will” and that the devil targeted the weakest–children, women, the mentally unstable–for the infliction of his evil deeds. The notion of the devil was not an abstract metaphor for evil. Sermons and writings, such as prominent Boston minister Cotton Mather’s book, Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions, explained that he and witches lived among the people.

The typically strict application of the Puritan code was reflected in many ways: the dark and somber style of dress, the repression of opinions and emotions, and the conviction that all sins were to be punished. Consistent with this often rigid code were the beliefs that if a neighbor suffered crop failure or the death of an infant, it was “God’s will” and that the devil targeted the weakest–children, women, the mentally unstable–for the infliction of his evil deeds. The notion of the devil was not an abstract metaphor for evil. Sermons and writings, such as prominent Boston minister Cotton Mather’s book, Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions, explained that he and witches lived among the people.

The spiral of events that led to the trials began on January 20, 1692, when the local minister’s daughter, Elizabeth Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams, began exhibiting bizarre and troubling behavior. The girls, aged nine and eleven, would suddenly shout blasphemy and make other strange sounds. They also would go into convulsions and contort their bodies into odd positions. Soon, other young girls in Salem Village displayed similar behavior.

Elizabeth and Abigail were examined by doctors but no physical cause to their continuing problems could be found, so the suspicion was that it was of a supernatural source (recent scholarship suggests that the girls behavior may have been resulted from attention-seeking, abuse, stress, psychosis, or ingestion of a fungus associated with rye wheat that is found in the area.) Elizabeth’s father, the Reverend Samuel Parris, ordered that a “counter-magic” be created, in the form of a cake made with rye meal and the girls’ urine, that would lead them to reveal those who afflicted them. It was Tituba, the Parris family’s Caribbean slave, they finally said, and they also implicated homeless beggar Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, an elderly widow who rarely attended church and had long been in dispute with the prominent Putnam family of Salem Village. Good and Osborne steadfastly maintained their innocence, but Tituba confessed to practicing witchcraft and claimed that there were other witches in Salem. An incendiary atmosphere followed that engulfed scores of other people in accusations. Jails quickly filled beyond capacity.

A special court was established to try the witchcraft cases. Included in the testimony was the spectral evidence, in which accounts from dreams or supernatural activity was admitted. None of those tried were found innocent. Accusations of witchcraft–likely often based on petty grievances and nurtured in the atmosphere of growing hysteria–spread and so did the hangings on Gallows Hill, beginning with the June 10 execution of Bridget Bishop. On July 19, five more women were hanged.

A special court was established to try the witchcraft cases. Included in the testimony was the spectral evidence, in which accounts from dreams or supernatural activity was admitted. None of those tried were found innocent. Accusations of witchcraft–likely often based on petty grievances and nurtured in the atmosphere of growing hysteria–spread and so did the hangings on Gallows Hill, beginning with the June 10 execution of Bridget Bishop. On July 19, five more women were hanged.

Exactly one month later, five others were killed, including an accused wizard, George Burroughs, who confounded witnesses by perfectly reciting the Lord’s Prayer, which was thought to be impossible by a person in conspiracy with Satan. On August 19 another suspected wizard, the elderly Giles Corey, who refused to stand trial because of the outrageous nature of his charges, received his punishment: being slowly pressed to death between two giant stones. A little over a month later, on September 22, the final four victims of the Salem Witchcraft Trials were hung. By the time it finally ended, the Salem Witchcraft Trials claimed the lives of 24 people; 20 by execution, four who died in jail, and two dogs that were considered possessed.

In the aftermath of the trials, many of Salem Village’s people were filled with regret for their participation or complicity in the events of 1692. Not Cotton Mather, however. Following the trials, he was provided by a few of the judges who were his friends with the records of the cases. In 1693, Mather wrote The Wonders of the Invisible World, which defended the trials and described New England as just one site where battles between God and the devil will be waged. Wrote Mather:

And we have now with horror seen the discovery of such a witchcraft! An army of devils is horribly broke in upon the place which is the…the firstborn of our English settlements. And the houses of the good people there are filled with the doleful shrieks of their children and servants, tormented by invisible hands, with tortures altogether preternatural. After the mischiefs there endeavored, and since in part conquered, the terrible plague of evil angels has made its progress into some other places, where other persons have been in like manner diabolically handled.

Despite Mather’s influence, the Salem Witch Trials were increasingly viewed as a dark mark of shame. In 1697, the Massachusetts colonial legislature passed a resolution for a day of fasting to repent for the cruel injustices perpetrated on those killed and accused during the witchcraft hysteria of five years earlier. In 1711, the Massachusetts legislature passed a bill to clear names of those persecuted and to provide ample restitution to their families. In 1957–over a quarter of a millenium after the trials–that state of Massachusetts formally apologized. Four years earlier, playwright Arthur Miller’s popular parable “The Crucible” applied the Salem Witchcraft Trials to serve as the setting for a modern example of “witch hunting”–the McCarthyism era of Cold War crippling fear, reckless accusation, and personal destruction.

In 1837, the great American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne–the great-great grandson of one of the Salem Witch Trials judges–captured the human capacity for evil, rooted in fear, that had tightened the nooses on Gallows Hill almost a century-and-a-half earlier and have continued to haunt us since. “In the depths of every heart,” wrote Hawthorne, “there is a tomb and a dungeon, though the lights, the music, and revelry above may cause us to forget their existence, and the buried ones, or prisoners whom they hide.”