“These are the times that try men’s souls.” – Thomas Paine, December 23, 1776

As the Revolutionary War began, there were few knowledgeable observers of the conflict who believed that the ragtag collection of citizen-soldiers would stand a chance of ultimate success against the greatest war machine in the world.

As the Revolutionary War began, there were few knowledgeable observers of the conflict who believed that the ragtag collection of citizen-soldiers would stand a chance of ultimate success against the greatest war machine in the world.

But in the first months of the Revolutionary War the Americans, motivated by a strong sense of purpose and fighting on familiar terrain, managed to impress some of their British enemies. Led by Vermont frontiersman Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold, who would later gain infamy as a traitor to the Revolution, American forces seized a much-needed stash of artillery at the weakly defended Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775. The following month, the rebels allowed the British only a Pyrrhic victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill, providing further evidence to the British that their American adversaries could be fierce and shrewd fighters. Remarking on the American fortification of Dorchester Heights that forced the British evacuation of Boston in the spring of 1776, General William Howe remarked, “The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army could do in months.”

But soon, unforgiving obstacles arose for the revolutionaries. The most formidable of these was the wealth, power, and organization of British fighting forces. Americans also had problems with the non-British enemies in their midst, including approximately eight thousand German mercenary soldiers, known as Hessians, and thousands of Tories, perhaps 20 percent of the colonial population, who remained loyal to the British. Countless Native Americans also sided with the British, viewing them as less likely to overrun their lands. They were especially effective as skilled guides and proficient frontier fighters. Americans also had difficulty replenishing troops and supplies during the often chaotic and ferocious engagements of the Revolutionary War. By the middle of 1776 the combination of these factors helped turn the tide of the war toward the British, who drubbed the rebels at the Battle of Long Island and forced the Americans to retreat from New York City.

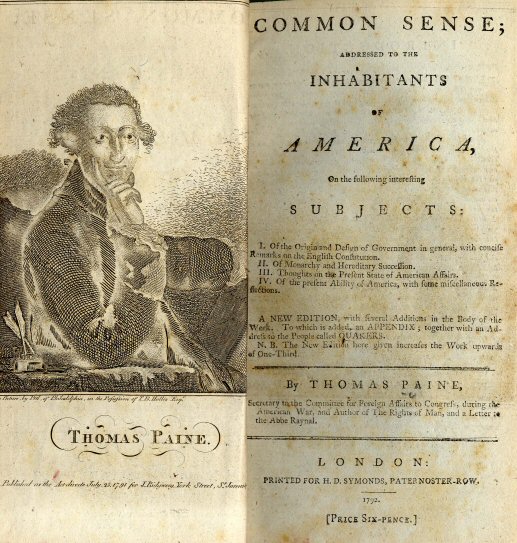

Helping to sustain the Americans during this dreary period were two men whose contributions to the revolutionary cause is incalculable: Thomas Paine and George Washington. Paine was thirty-six years old in 1774 when he came to Philadelphia from England after failing at a variety of jobs. In January 1776 he wrote a politically radical pamphlet, Common Sense, expressing in plain words a compelling vision in which ordinary people not only participate in government, but are the power of the government. A particular target of Paine’s scorn was monarchies: “How a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest and distinguished like some new species is worth enquiring into. . . . Of more worth is one honest man to society . . . than all the crowned ruffians who ever lived.” Such subversive ideas resonated with the common people in the American colonies, who purchased over 100,000 copies of Common Sense within three months of its publication.

Helping to sustain the Americans during this dreary period were two men whose contributions to the revolutionary cause is incalculable: Thomas Paine and George Washington. Paine was thirty-six years old in 1774 when he came to Philadelphia from England after failing at a variety of jobs. In January 1776 he wrote a politically radical pamphlet, Common Sense, expressing in plain words a compelling vision in which ordinary people not only participate in government, but are the power of the government. A particular target of Paine’s scorn was monarchies: “How a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest and distinguished like some new species is worth enquiring into. . . . Of more worth is one honest man to society . . . than all the crowned ruffians who ever lived.” Such subversive ideas resonated with the common people in the American colonies, who purchased over 100,000 copies of Common Sense within three months of its publication.

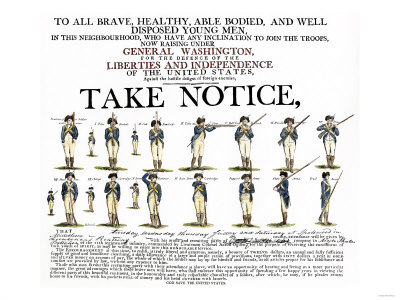

Paine’s words also helped spur recruiting efforts for the newly formed Continental Army headed by General George Washington. Although the army was growing, it still faced daunting odds, and Washington himself had been reluctant to take command of it. Privately he expressed anguish over the quality and condition of his soldiers, commenting during the American defeat in the Battle of Long Island, “Good God! Are these the men with whom I am to defend America?”

Publicly, however, Washington possessed the rare and critical qualities of great leaders—sharp tactical insight and the ability to inspire confidence and loyalty among his charges. Washington realized early in his command that he would have to organize the troops differently because of the Americans’ lack of resources. He recognized the need to “prolong the war as long as possible” by avoiding unnecessary risk while wearing down British resolve. Washington also became highly reliant on the motivation and personal engagement of his troops and the local population.

Among the tactics Washington employed was to have his troops read the words of Thomas Paine, who accompanied Washington and his weary forces during the cold campaigns in late 1776. Paine’s essay “The American Crisis” originally penned on a drumhead, simultaneously summarized and invigorated the revolutionary effort during its bleakest hour:

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly.”

In late December, with the Continental Army reduced by casualties and captures, Washington decided to go on the offensive. Overcoming freezing weather, he and his troops clandestinely crossed the Delaware River under the cloak of night to launch a successful surprise attack at Trenton, New Jersey. Washington then addressed his beleaguered soldiers, whose enlistments would soon expire, making them free to leave: “You have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected, but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you.”

In late December, with the Continental Army reduced by casualties and captures, Washington decided to go on the offensive. Overcoming freezing weather, he and his troops clandestinely crossed the Delaware River under the cloak of night to launch a successful surprise attack at Trenton, New Jersey. Washington then addressed his beleaguered soldiers, whose enlistments would soon expire, making them free to leave: “You have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected, but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you.”

The regimental drums rolled, but no one moved. Men exchanged glances before the drums beat again. Whether because of shared adversity, dedication to the cause, or belief in General George Washington, one man stepped forward, then another. Within moments, every able-bodied soldier had volunteered to continue the fight.