“How can a government go on, publishing all of their negotiations with foreign nations, I know not.” – John Adams, December 19, 1793

The recent disclosure of over 250,000 secret U.S. government documents by WikiLeaks, many of which have been published in the New York Times, has understandably received a great deal of attention. The publication of classified material by the Times had led many people to compare the WikiLeaks case to the most prominent document leak in American history, in what became known as the Pentagon Papers case. But as a leading American journalist and the U.S. Secretary of Defense pointed out this week, these comparisons are limited at best and inaccurate at worst.

The recent disclosure of over 250,000 secret U.S. government documents by WikiLeaks, many of which have been published in the New York Times, has understandably received a great deal of attention. The publication of classified material by the Times had led many people to compare the WikiLeaks case to the most prominent document leak in American history, in what became known as the Pentagon Papers case. But as a leading American journalist and the U.S. Secretary of Defense pointed out this week, these comparisons are limited at best and inaccurate at worst.

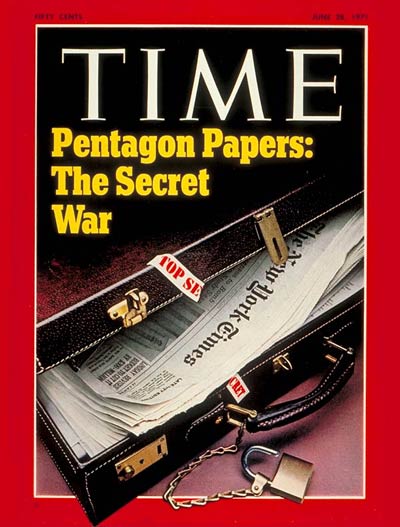

The Pentagon Papers were a top-secret U.S. government study tracing American involvement in Southeast Asia, specifically Vietnam, from World War II to May 1968. It was ordered by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in June 1967 and was written for over a year and a half by a team of analysts who had access to classified documents. The study showed that U.S. presidents and high ranking civilian and military leaders had miscalculated the risks and conditions of military involvement in Vietnam and misled the American people about the U.S. role throughout the region.

Excerpts from the study were secretly given to the New York Times by Daniel Ellsberg, who was one of the analysts involved in the research. On June 13, 1971, the Times began publishing a series of articles based on the documents, which became known as the Pentagon Papers. After the Times printed its third installment of the Pentagon Papers, the Justice Department of President Nixon’s administration asked for and received a restraining order to prevent the newspaper from publishing material based on the study. If the Times published the remaining articles in its series, the government argued, it would bring “immediate and irreparable harm” to the “national defense interests of the United States and the nation’s security.”

Excerpts from the study were secretly given to the New York Times by Daniel Ellsberg, who was one of the analysts involved in the research. On June 13, 1971, the Times began publishing a series of articles based on the documents, which became known as the Pentagon Papers. After the Times printed its third installment of the Pentagon Papers, the Justice Department of President Nixon’s administration asked for and received a restraining order to prevent the newspaper from publishing material based on the study. If the Times published the remaining articles in its series, the government argued, it would bring “immediate and irreparable harm” to the “national defense interests of the United States and the nation’s security.”

This constitutional conflict quickly was reviewed by the Supreme Court in the case of New York Times v. United States. In its petition to the Court, the government asserted that it should be the sole judge of national security needs and should be granted a court order to enforce that viewpoint. The Times countered that this would violate First Amendment press freedoms provided for under the U.S. Constitution. It also argued that the real government motive was political censorship rather than protection of national security, explaining that much of the information contained in the Pentagon Papers had already been reveled by government officials themselves.

On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the New York Times, and the documents were subsequently published. In allowing the newspaper to continue the series the Court noted how the Constitution has a “heavy presumption,” in favor of press freedom. The Court left open the possibility that dire consequences could result from publication of classified documents by newspapers, but it said that the government had failed to prove that result in this instance.

Time’s Fareed Zakaria draws clear and important contrasts between the Pentagon Papers and the recent Wikileaks disclosures:

First, there is little deception. These leaks have been compared to the Pentagon papers. Which they are not. The Pentagon papers revealed that the U.S. engaged in a systematic campaign to deceive the world and the American people and that its private actions were often the opposite of its stated public policy. The WikiLeaks documents, by contrast, show Washington pursuing privately pretty much the policies it has articulated publicly. Whether on Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan or North Korea, the cables confirm what we know to be U.S. foreign policy. And often this foreign policy is concerned with broader regional security, not narrow American interests. Ambassadors are not caught pushing other countries in order to make deals secretly to strengthen the U.S., but rather to solve festering problems.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates expressed a similar view of the WikiLeaks/Pentagon Papers comparison and expanded historical connections more broadly and convincingly, noting this week:

…in all of these [WikiLeaks] releases, whether it’s Afghanistan, Iraq or the releases this week, [there is a] lack of any significant difference between what the U.S. government says publicly and what these things show privately, whereas the Pentagon Papers showed that many in the government were not only lying to the American people, they were lying to themselves.

But…let me just offer some perspective as somebody who’s been at this a long time. Every other government in the world knows the United States government leaks like a sieve, and it has for a long time. And I dragged this up the other day when I was looking at some of these prospective releases. And this is a quote from John Adams: “How can a government go on, publishing all of their negotiations with foreign nations, I know not. To me, it appears as dangerous and pernicious as it is novel.”

When we went to real congressional oversight of intelligence in the mid-’70s, there was a broad view that no other foreign intelligence service would ever share information with us again if we were going to share it all with the Congress. Those fears all proved unfounded.

Now, I’ve heard the impact of these releases on our foreign policy described as a meltdown, as a game-changer, and so on. I think – I think those descriptions are fairly significantly overwrought. The fact is, governments deal with the United States because it’s in their interest, not because they like us, not because they trust us, and not because they believe we can keep secrets.

Many governments – some governments deal with us because they fear us, some because they respect us, most because they need us. We are still essentially, as has been said before, the indispensable nation. So other nations will continue to deal with us. They will continue to work with us. We will continue to share sensitive information with one another. Is this embarrassing? Yes. Is it awkward? Yes. Consequences for U.S. foreign policy? I think fairly modest.