“Memory is often less about truth than about what we want it to be.” – David Halberstam, October 21, 2000

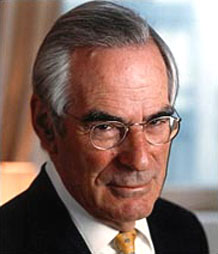

Last Friday marked three years since the great journalist and historian David Halberstam died in a car crash in Menlo Park, California. Halberstam, a Pulitzer Prize winning reporter early in his career, later wrote over twenty books about American history and sports. He was in northern California at the time of the accident to conduct research for his book, The Glory Game: How the 1958 NFL Championship Changed Football Forever (eventually written by Halbertam’s friend, former football star and broadcaster Frank Gifford.) Halberstam was on his way to interview former New York Giants quarterback Y.A. Tittle, when the car he was a passenger in was broadsided and forced into a third vehicle, killing him at the scene.

Last Friday marked three years since the great journalist and historian David Halberstam died in a car crash in Menlo Park, California. Halberstam, a Pulitzer Prize winning reporter early in his career, later wrote over twenty books about American history and sports. He was in northern California at the time of the accident to conduct research for his book, The Glory Game: How the 1958 NFL Championship Changed Football Forever (eventually written by Halbertam’s friend, former football star and broadcaster Frank Gifford.) Halberstam was on his way to interview former New York Giants quarterback Y.A. Tittle, when the car he was a passenger in was broadsided and forced into a third vehicle, killing him at the scene.

An incredibly diligent and detailed researcher and a master of clear, compelling storytelling, Halberstam’s books were– at the time of their publishing and since–among the best and ahead-of-their time in their respective topics. His 1972 book The Best and the Brightest expansively exposed origins and the tragic folly of American intervention in the Vietnam War. In 1979 he wrote The Powers That Be that examined the rise of modern American media and its relation to political power and his 1986 book The Reckoning detailed the vulnerability of the American auto industry in the face of challenges from Japanese competition.

Halberstam’s 1993 book The Fifties stands as a particularly impressive treatment of history. In a July 1993 interview with C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb, Halberstam explained how he envisioned this book as, “[looking] at America when it was rich in a world that was poor, when everything seemed to work…there would be sections on television…affluence..the McCarthy period, and if possible, near the end of the book they would begin to twine together…they would braid, so that you have television and then you would have civil rights, and then late in the book television would be covering civil rights.” I imagine how much Halberstam would have loved the television show Mad Men,which debuted a few months after his death. Though the show began set in the early 1960s, it captures and reflects so much of what he described in the preface to The Fifties as “the social ferment…[that] was beginning just beneath this placid surface…[when] many people were already beginning to question the purpose of their lives.”

Halberstam’s 1993 book The Fifties stands as a particularly impressive treatment of history. In a July 1993 interview with C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb, Halberstam explained how he envisioned this book as, “[looking] at America when it was rich in a world that was poor, when everything seemed to work…there would be sections on television…affluence..the McCarthy period, and if possible, near the end of the book they would begin to twine together…they would braid, so that you have television and then you would have civil rights, and then late in the book television would be covering civil rights.” I imagine how much Halberstam would have loved the television show Mad Men,which debuted a few months after his death. Though the show began set in the early 1960s, it captures and reflects so much of what he described in the preface to The Fifties as “the social ferment…[that] was beginning just beneath this placid surface…[when] many people were already beginning to question the purpose of their lives.”

When I noticed the anniversary of Halberstam’s death, I sought a quote of his that would form the foundation of a meaningful and interesting post for this site. Though his book title, The Best and the Brightest is the most identifiable and enduring phrase associated with him, I decided to choose a line he wrote in an October 21, 2000 essay in the New York Times entitled, “Maybe I Did See DiMaggio’s Kick.” In the piece, Halberstam–who was an avid sports fan and author of several excellent sports history books including The Breaks of the Game and October 1964–describes his possibly false recollection of being in the Yankee Stadium stands during the 1947 World Series and witnessing one of the most famous plays in World Series history.

Wrote Halberstam:

A huge roar went up from the Yankee partisans in the bleachers, and then, as Al Gionfriddo made his celebrated catch, it seemed to ebb and turn into a gasp, while from the same section a second roar of approval exploded from the Dodger fans seated right there with us. Did I actually see the catch? I think I did. Did I see DiMaggio famously kick the dirt as he reached second, a moment replayed on countless television biographies of him because it was the rarest display of public emotion on his part? Again, I think I did. Who knows? Memory is often less about truth than about what we want it to be.

This quote resonated strongly with me recently thanks to a few recent conversations with friends. In the first, a friend recommended that I watch the 2009 Israeli movie “Waltz With Bashir,” an animated documentary centering on the movie creator Ari Folman’s struggle recalling his experience as an Israeli soldier in Lebanon during the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres of Palestinians and Muslims by Christian Lebanese forces. In addition to being among the most interesting, unique, and best movies I’ve seen in a long time, “Waltz With Bashir” is a profound but accessible exploration on the nature of memory–what we remember and why; what we repress and why. French movie critic Serge Kaganski wrote of “Waltz With Bashir” that it is “A clever work of (and about) memory a powerful, beautiful…film” and A.O. Scott of the New York Times described it as, “A memoir, a history lesson, a combat picture, a piece of investigative journalism and an altogether amazing film.”

This quote resonated strongly with me recently thanks to a few recent conversations with friends. In the first, a friend recommended that I watch the 2009 Israeli movie “Waltz With Bashir,” an animated documentary centering on the movie creator Ari Folman’s struggle recalling his experience as an Israeli soldier in Lebanon during the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres of Palestinians and Muslims by Christian Lebanese forces. In addition to being among the most interesting, unique, and best movies I’ve seen in a long time, “Waltz With Bashir” is a profound but accessible exploration on the nature of memory–what we remember and why; what we repress and why. French movie critic Serge Kaganski wrote of “Waltz With Bashir” that it is “A clever work of (and about) memory a powerful, beautiful…film” and A.O. Scott of the New York Times described it as, “A memoir, a history lesson, a combat picture, a piece of investigative journalism and an altogether amazing film.”

The next week, I was discussing the movie with my friend who recommended it and another friend. Describing the movie’s treatment of memory led me to recall the book The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. The highly-acclaimed book about the author’s experience as an American soldier during the Vietnam War is a singular mix of fiction, autobiography, even fantasy, that like Halberstam’s best work, braids various elements of memory and storytelling into a powerfully coherent work, though in a far more literary, rather than directly historical way. The New Yorker’s review of The Things They Carried noted, “O’Brien’s absorbing narrative moves in circles; events are recalled and retold again and again, giving us a deep sense of the fluidity of truth and the dance of memory.” From Publishers Weekly’s review, “O’Brien’s meditations–on war and memory, on darkness and light–suffuses the entire work with a kind of poetic form, making for a highly original, fully-realized novel…Beautifully honest…This book is persuasive in its desperate hope that stories can save us.”

The next week, I was discussing the movie with my friend who recommended it and another friend. Describing the movie’s treatment of memory led me to recall the book The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. The highly-acclaimed book about the author’s experience as an American soldier during the Vietnam War is a singular mix of fiction, autobiography, even fantasy, that like Halberstam’s best work, braids various elements of memory and storytelling into a powerfully coherent work, though in a far more literary, rather than directly historical way. The New Yorker’s review of The Things They Carried noted, “O’Brien’s absorbing narrative moves in circles; events are recalled and retold again and again, giving us a deep sense of the fluidity of truth and the dance of memory.” From Publishers Weekly’s review, “O’Brien’s meditations–on war and memory, on darkness and light–suffuses the entire work with a kind of poetic form, making for a highly original, fully-realized novel…Beautifully honest…This book is persuasive in its desperate hope that stories can save us.”

Each of these works shares a common quality with Halberstam’s writing: a desire to learn the truth about history and ourselves that co-exists, but does not succumb to, the sometimes inevitable constraints of that quest. It is the sober recognition of these limits that inform and enrich understanding and lead to wider paths of curiosity and discovery.